Tags

academia, awards, etiology, genetics, lipoproteins, public health, success, type II diabetes, winning awards

Yee-ha. 3.5 weeks’ in to IT, life must be slowly returning to normal (the new normal, to be cliched) as I actually have something about academia to say. My mind must be emerging from its previous state where it basically went “How is Sam?…. is Sam OK…? Do I need to feed Sam?… Maybe I’ll just look at Sam for a while… Awwww… look at Sam! [repeat ad infinitum]”. I have even managed some work. It is good to be back 🙂

So, I recently won an award. The Scott Grundy Fellowship Award for Excellence in Metabolism Research, given by the American Heart Association (AHA). I am ridiculously excited (hey – I have been in with a baby for nearly a month, it doesn’t take much!). But… I feel a bit guilty because I don’t think my research is any better than many of the other applicants (and I know this because I graded the abstracts for the conference, and saw some of the abstracts which applied for this award, although obviously I had no say in the actual award). I have felt like this before… I have won a few awards in my time (and even had some taken away :-O ), and really, I am not sure I ‘deserve’ any of them. So as a way to assuage my guilt here are my ‘hot tips ‘n’ tricks’ for winning academic awards at a junior level:

1. Make your submission a culmination of a body of work. Random projects may be very good, but IME, they rarely win awards. At the junior level at least, it is better to have had a clear path to the current the piece. Notice how many people win at the end of their PhD.

2. Make it clear how you are going to further this work. A lot of awarding bodies want to give the award to someone whose work will become well-known. So, it is best to make it clear that you – and others – think this work has real longevity (for epidemiologists read: clinical implications). Spell out how these conclusions will lead to work that will eventually help people and how YOU will use it to do so.

3. Apply for everything. Seriously. To an extent: it is a numbers game. No one knows what you didn’t get, they only know what you did. Any competition, any award, any conference with a ‘prize’, anything: I’ll apply for. Kind of the infinite monkeys theorem approach . Yes, it is awkward to nominate yourself for an award. Read this for inspiration to do so.

4. Know the awarding body you are applying to, and know their mission. Use phrases from their website / literature / position statements for how your research fits their mission.

5. Know the ‘hot trends’ in your fields, and try to submit a paper on that (without ignoring point 1). Ah… yes, my paper is on ethnic disparities.

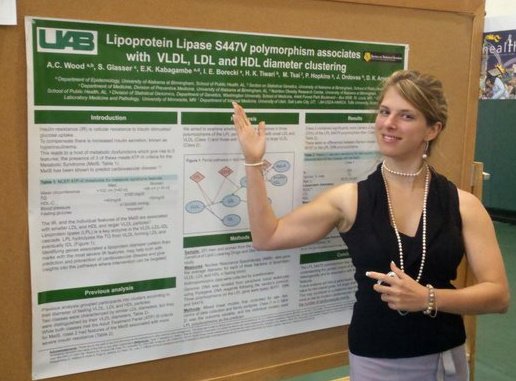

My early postdoc work… and the starting point for the winning abstract. Yes, it was a long research road.

6. Know the politics of your awarding body. Do they like certain studies more than others? I’ll be honest: I had heard that certain data-sets were more popular with the AHA than others… so I shamelessly planned to submit an abstract from one of those data-sets (although it is also true that this data-set was the best – and maybe only – way to answer the question I was interested in). Cold.

7. Think carefully about your letters of support and don’t brush over them. Choose your referee(s) wisely: I had an extremely gifted referee who was very respected by the AHA. He also wrote a wonderful – and personal – letter. This was really what did it, I suspect. I have seen people at other conferences ‘win’ or be a ‘Young Investigator Finalist’ and, especially with people finishing their PhDs, am sure that it is partially because their mentor is extremely popular in the society. Do not be afraid to ‘help’ your referee see the value and place of your work, either 🙂

8. Be involved in the awarding body, if you can. Go to their conferences, publish in their journals (er… I am failing at this one…) and help their society if you can.

So, I write this out, and it all sounds horrible. Clearly I decided I wanted an award and went for it, well before the submission date. I know I would love to think that awards were won solely because a brilliant young Scientist did some ground breaking research in a moment of inspiration that wowed the conference / society. But, realistically I don’t see this to be the case all the time (or even much?). So, I invite people to play the game others are playing: it only seems fair.

Also, of course, following all the above to the letter is NOT going to let bad research win. It is just going to help the very good research stand out a little.

My work:

Oh, what work won this award? Well, I have this hunch that patterns of lipoprotein sizes can be used to detect early diabetes: that is small LDL, in conjunction with large VLDL and small HDL may help us better identify who is at risk for Type 2 diabetes. I would like to develop this as a diagnostic, or at least, clinically predictive, test. I don’t know if it will work, or be better than our current clinical measures, but for some time, I have been interested in this pattern of lipoproteins, and interested in whether etiology (i.e. the causes – genetic and otherwise) are the same for small LDL as for small HDL as for large VLDL. This is primarily what I worked on during my postdoc. I am now interested in ethnic disparities in lipoprotein patterns: my work was previously all in Caucasian-Americans: is the same pattern predictive in non-Caucasian Americans? I need to know this because if I want to develop a diagnostic test, I need to know who it applies to, of course, I aim to develop a test that applies to all populations.

And then the topic of the ‘winning’ abstract,which has been the subject of my faculty research thus far: is the etiology of lipoproteins different by race / ethnicity? And if so: why? Does it speak to gene-environment interactions and so does it point to more modifiable risk factors (e.g. diet and exercise, but maybe something more exciting) in helping to prevent incident Type II Diabetes?

Image credit